“On the Trail of Henry Knox” by Jennifer Dorsen (1 of 5)

In which My Interest in Cannons is Piqued and Somerville Pride Bruised.

Even though Somerville sits at the strategic heart of Revolutionary War Boston, it is often overlooked. It is also understandable; we sit between our neighboring cities of Lexington, Cambridge, and Boston, all of which deserve plenty of glory. Interest in Somerville’s Revolutionary-era history seems to emerge every 50 years, along with national remembrances of the play-by-play events of 1774-1776, and last year was one of those times. A neighbor of mine thought that Somerville, given its centrality, should have a “Freedom Trail” of its own, so I spearheaded a map project with the Somerville Museum to document the many sites of interest related to Revolutionary and pre-Revolutionary history in Somerville and Medford. (The “History on the Line” map can be found here).

As the 250th anniversary of the Revolution approached, I wanted to learn more about those foundational days and why they remained so compelling. Few countries have a “moment of origin” like the USA does, emerging from that soup of big, often competing ideas: democracy-monarchy, freedom-slavery, war-peace, leadership-followship. I learned the history as I went, digging into the stories as I explored. Among the many interesting stories, one location caught my attention, that of Cobble Hill. We know Cobble Hill not as a hill at all, but rather the flat location of an apartment complex built in 1981, a tangle of railroad spurs and light industrial sites on land levelled and expanded by infill. Some new development is making inroads, but it’s still a bit lawless where you don’t need a permit to park a truck overnight.

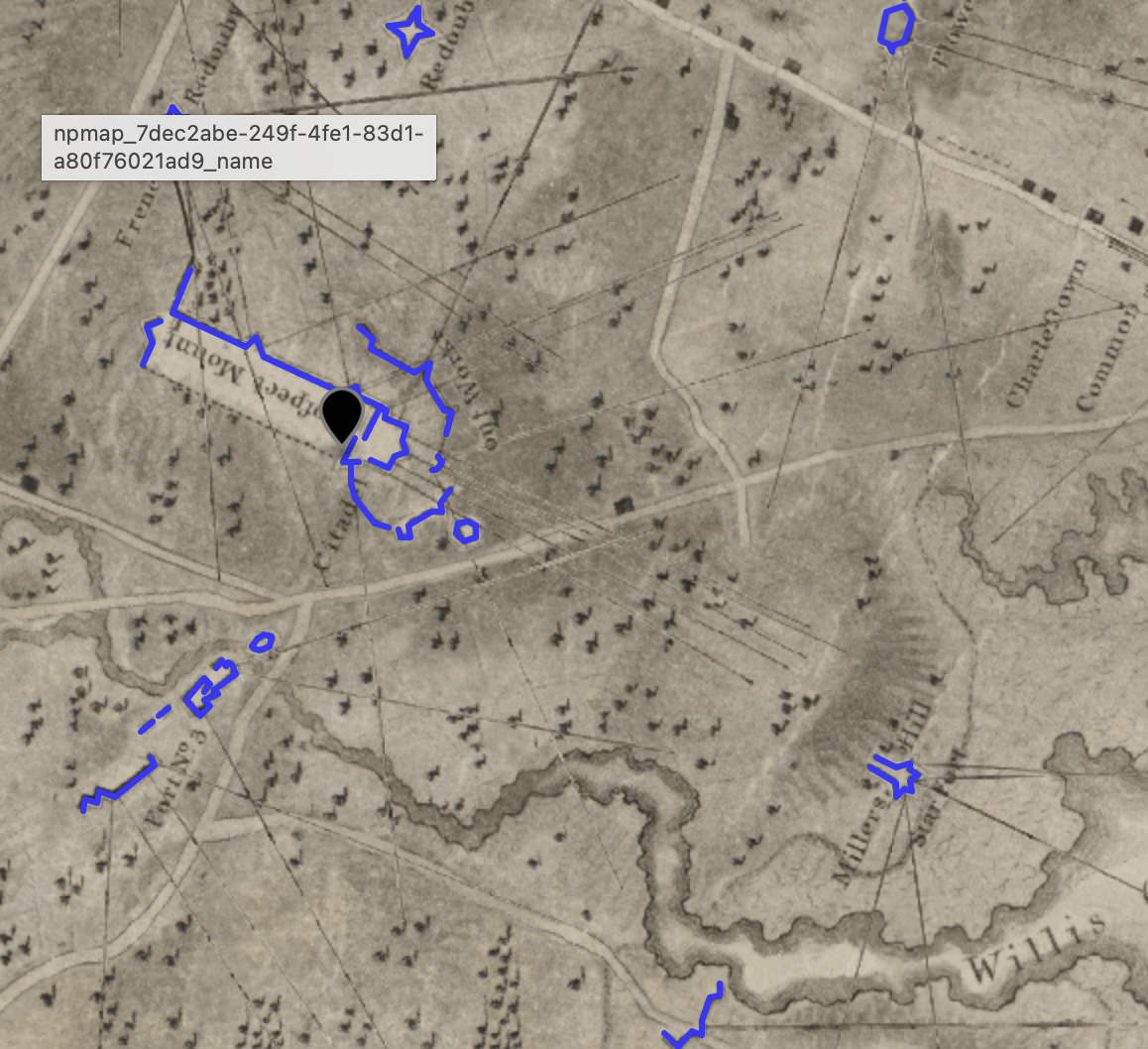

In 1774-1776, the scene was quite different. Cobble HIll was 50 feet high above the marshes along the Charles River, sloping sharply down to the river’s edge overlooking Boston and the river. Small farms lined what is today Washington Street, the main road between Charlestown and Union Square, with Harvard Square beyond. The Revolutionary story of this hill picks up after the Battle of Lexington and Concord (recall the results: Revolutionaries, One: British, Zero.), when the hills of today’s Somerville were transformed into war fortifications for soldiers: mess halls, barracks, hospitals, training grounds, prisons, stone reinforcements in four fort areas: Winter Hill, Prospect Hill, Ploughed Hill, and Cobble Hill. About 4000 soldiers lived in the area during the Siege of Boston from June 1775 to March 1776, through an especially cold winter.

Continental Army Fortifications in what is now Somerville during the Revolutionary War

The Siege of Boston started with the Battle of Bunker Hill in June, 1775 and ended with Evacuation Day, March 17th, when - as we learned in school - the British, trapped on the Boston peninsula, awoke surrounded by cannons that had been put into place overnight on Dorchester Heights. Overwhelmed, they boarded ships and left. Revolutionaries: two.

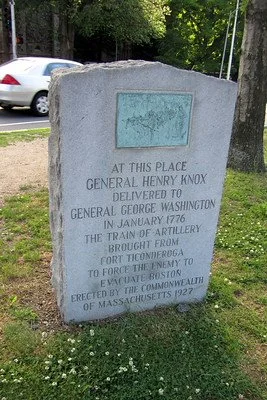

The cannons themselves - all 60 tons of brass, lead cannon balls, and other armaments - had been dragged 600 miles from Fort Ticonderoga near Burlington, Vermont by an unlikely hero, Henry Knox. Knox was a 25-year-old Boston bookseller with no leadership experience who recruited sets of volunteer locals with their horses and oxen to support the mission. Starting on December 6, 1775, they slid the length of Lake George on the ice, then pulled the cannons up the west side of the Berkshires just north of Great Barrington, and across Massachusetts’ snowy hills and rivers roughly where the Mass Pike is today. After 56 days, they parked the cannons in Watertown, while Henry Knox went into Cambridge to General George Washington's Headquarters to report that his “Noble Train of Artillery” was ready. If this sounds amazing, it is. Historians have called this mission "one of the most stupendous feats of logistics" of the Revolutionary War.

Marker in the Cambridge Common where Knox handed over his “Noble Train of Artillery” to General George Washington

But back to Somerville. Given Somerville was in the strategic center of this conflict, did any of those cannons sit on Cobble Hill? A few secondary sources said yes while others said no. None cited their original source material to check. Finding original source materials was going to be a challenge. Knox himself kept a diary of events, but after Springfield (mid-January), he barely wrote. Which was it?

As I researched, my Somerville pride was bruised. Some historical sources claimed that Cobble Hill was in Cambridge or obfuscated its location. I got curious to get to the bottom of it all. If it was true, then let’s find the original source material and literally put Somerville back on the map of Henry Knox’s Noble Train of Artillery, and if not true, then let’s be clear about that. I had high hopes that we would find that Cobble Hill was in fact one of the terminals of the Noble Train, and that we would be designing a marker to join the other 56 along the route, erected in 1926-27, the 150th anniversary of the Noble Train.

The search was on!